Their story is one of serial triumphs over adversity. The Depression of the 30s saw staff working one week on, one week off. Recovery was thwarted by an exodus of personnel to the front lines of World War II, during which many businesses who patronised them were destroyed in bombing raids.

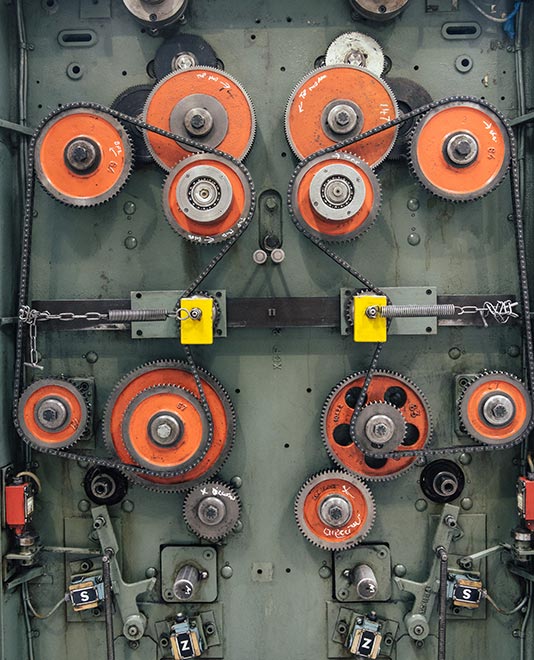

Decades of growth followed, but around the time James Laxton – the fourth generation of the family to run the company – took the helm in 1992, a grim stint in the United Kingdom’s textile industry unfolded, culminating in Laxtons’ manufacturing activities shutting down altogether. “For ten years or so it was all off-shored – we were just an office, working with Spanish, South African and Turkish mills creating yarn to our specifications,” explains sales director Alan Thornber. And yet, in spring 2017, 110 years after the company was founded by George Laxton and Gordon Holmes, the cogs and conveyor belts in the company’s brand new, 16,000 sq ft, state-of-the-art new spinning mill in Baildon, West Yorkshire creaked into action.

Laxtons specialises in worsted and ‘fancy’ yarns (the latter has nothing to do with the colloquialism in this part of Britain for ‘posh’ – it refers, rather, to structural effects such as bouclé). It is a highly sophisticated operation, which begins with raw bales of fabric arriving from all across the world. “We source wool from Australia, The Falkland Islands and use British wool too, and alpaca, silk or mohair from South Africa, China and elsewhere,” says Thornber, taking us up to a mezzanine floor on which bales containing 400 or 500 kilos of fibre are stacked in neat piles.

“Because we’re a niche producer, a lot of our customers need something made from a specific type of sheep because of the different characters they offer. A breed that’s good for knitwear is not going to be best for carpets; some customers like a soft handle, so they need wool from a Bluefaced Leicester breed; others want a lustrous effect and therefore require a Wensleydale wool; a Merino gives amazing bounce and elongation.” Laxtons’ service, he says, is effectively bespoke. “We don’t make yarns and then ask people to buy them – our customers come to us and say ‘We want to produce socks’ or ‘Our speciality is upholstery that has a bit of texture’, and then we’ll explain to them what we need to be using to provide that. They know what they want – we know how to choose the wool to make it happen.”

The fibre, having been weighed out in quantities dictated by recipes, is sent via vertical chutes to a vast ground-floor working space where engineering precision and human judgement make a dynamic duo. “There’s no automated doffing and robotics in this place,” says Thornber. “We can’t leave our machinery to its own devices because we’re working with natural fibres. If we were working with man-made fibres, our machines could run about ten times as fast, in a much more automated way. You have to treat wool much more carefully, though.”

Gallery

Why? “Because every bale we receive, even if it has exactly the same label, is different,” he explains. “The wool hasn’t grown on the same sheep in the same climate each time.” By way of illustration he takes us to a drafting machine, on which a rich, autumnal chestnut wool, blended from raw Merino fibres of rust, black, white and beige, is being carefully elongated by rollers, several feet apart and moving at different speeds.

“Processing one bale of Falkland wool one week then another of the same wool two weeks later, the machine may need different settings,” says Thornber. “There are differences in length, variation of length, moisture content, how long it’s been in the dye bath. These aren’t machines that just get switched on in the morning and switched off at night. You need the human touch, and staff with lots of experience.”

That’s not to say the technology here isn’t eyebrow-hikingly sophisticated, of course. Optical detection and auto-levelling equipment, at this stage in the process, ascertains whether the yarns are precisely the same diameter – if a thick portion is detected, the rollers will speed up slightly to stretch the yarn a fraction more, while for thin parts, it slows the rollers down. During the winding stage, meanwhile, after faults are removed from the yarn, pneumatic technology splices the loose ends together, eliminating the need for obtrusive knots.

Humanity’s relationship with wool dates back to primitive societies, and elsewhere in the factory we witness processes that demonstrate an intimate knowledge of how fleece behaves. Take the spinning and twisting stage, for example. When spinning, a spindle rotates anti-clockwise to follow a ‘Z’ direction; when twisting, it rotates clockwise, ensuring an ‘S’ direction. The result is a more balanced yarn, less prone to corkscrewing. If it does come out a little wayward (‘live’ is the technical word here), the time-honoured remedy, steaming – which also adds bulk, softness and volume – presents a tricky Goldilocks conundrum: too little exposure and it’ll remain wayward; too much and it yellows.

Once dried, the wool is wound using a machine whose settings have so many variables – angles, rotation circumferences, rotation speeds, drop heights – that Thornber describes the technician who repairs and maintains it as being “like a rocket scientist”. The resulting hanks and reels are then labelled, packaged, bar-coded, stickered and sent off for distribution. But Laxtons’ procedure doesn’t end there.

In a small testing room next to the factory floor, volumes of archives testify to the gravity of consistency – in terms of colour and texture as well as quality. “We keep samples of every batch we make,” explains Thornber, “so that we can address things and eradicate any problems.” It’s here, also, that Laxtons’ eagle-eyed quality control staff check fibre lengths as soon as batches of wool come in. “The fibres in a batch should be different lengths. It won’t spin properly if they’re identical, but we need the longest and the shortest fibres in a batch not to be too different to each other, too.”

This borderline-obsessive attention to detail typifies why Laxtons today, having undergone such a bumpy ride over the past century, is on a smooth track to a bright future. As recently as January this year, the machinery now assembled and laid out in procedural order on the shop fioor was in countless pieces. Today, around 25 staff are beavering away, turning high-quality raw fleece into yarns of such excellence that they are utilised by fashion giants such as Chanel, Louis Vuitton, Marc Jacobs and Paul Smith. It’s a high-functioning antidote to any notion that Britain’s textile industry is in the doldrums.